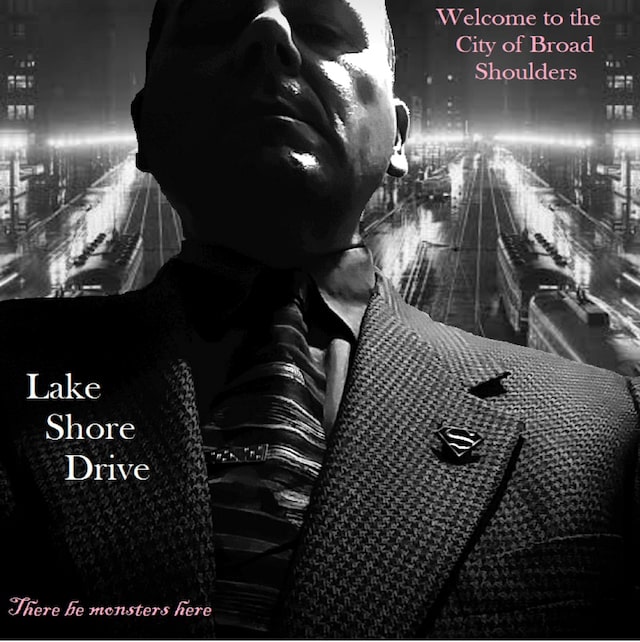

Lake Shore Drive – Episode One

Lake Shore Drive

Episode One

Goodbye To The Not Yet Emerald City

The porter rest his weathered and sea salted hands and gave the faintest of grips, trying to force some strength into this man.

This man–was he a man? The porter was no longer sure. Actually, upon meeting this fellow some years ago, he hadn’t known just what to make of him. The porter pressed firmly one more time. While doing this, he snaked out a pack of cigarettes from his uniform.

The man on the table shook his head as best he could but the restraints were tight. Tighter than usual he thought. But, he couldn’t be too sure. He couldn’t be too bothered either. “I…don’t…smoke.”

The man had clamps on his mouth (as requested), so speech was more difficult than usual. The porter stuck a cigarette right down into a nook and cranny of the gray fellow’s gray lips, making it look a little like a flagpole–one whose flag was burning incongruously in its surroundings. The man strapped down to the table, the gray man whose muscles were squirreled with taut veins running amuck all over his failing body–this man, wondered the porter, was he afraid of dying?

The man spit out the cigarette with a convulsed laugh.

The porter caught it in midair air and stuck into his own mouth. It stayed there erect, a conductor’s baton directing the lovely duet of laughter being now performed by the men. A sway of glee, a punctuation of snorts, the unbridled trombones of the belly roar…until finally the glee died down to almost nothing, leaving them to regard only the joke.

“Afraid of…dying?” the gray man asked.

“I know, I know friend, you don’t smoke because of the taste.” The porter began his exit, but then paused. Sighing, he asked, “Sure about this buddy?”

“Ah Hell,” the man said. “I’m leaving Seattle and moving to Chicago. It’s not like I’m dying. Well…” The old friends shook their heads quietly in understanding. Quiet eyes and stern noses, chins made for withstanding punches, hands seemingly born holding blades. But under the accoutrements, the fedoras, the tie clips, the oiled black leather shoes, the endless array of trench coats and blazers, vests, smoking jackets…these were not uniforms or part of an informal dress code: These were costumes. Their real selves were the kind polite people didn’t, and still don’t, talk about.

“I’ll send that witch of yours’ in then, said the porter.”

The gray man breathed, his eyes thought back to his childhood. “All right, I suppose I’m as ready as I’ll be.” Then, looking at the porter with sincere gratitude, he grimaced his grin and said, “Thanks Nels.”

Nels shook his head. He’d been a porter for many years now, really, too many. But, he’d never ported a person before. He did not care for it. He shook his head again. After all he’d seen the previous seven years, this really was nothing. He looked at his friend for perhaps the last time. His friend’s breath was almost unperceivable now, save for the small plumes of white exhale, which found his own plumes.

Before going to fetch the woman waiting patiently in the station, Nels slammed the train car door, slammed it hard, to prevent the ice from melting.

…

As the train barreled up and around and then through the mountains separating east from west, the gray man dreamed a thought. It wasn’t that he disliked Seattle, it wasn’t that he wouldn’t miss it. In fact, he felt the melancholia as he had not felt it for quite some time. But there was little opportunity for regret, less for tears, none for reflection. He had been called in. He had been called home. And, some calls could not be refused–even by him. His mind drifted further into the abyss as he felt the moon climbing down from the sky, her goddess would dismount her swan pulled chariot soon enough and although he had no fear of her twin brother the sun-god, he preferred the darkness night afforded him.

He could sense they were in one of the longer tunnels, could sense that he was in total blackness. The cold and dark wrapped themselves into a sailor’s knot around him and he cocooned in a meditative reverie for what he perceived to be hundreds of miles, hundreds of thousands of railroad ties.

…

Somewhere within the Wind River canyon–close to where the train line hugs the river, jagged and rough hills and small buttes confining them all, the conductor had to delay their travels due to wild mustangs crossing the tracks. The band was led by a black Bucephalus type so large the conductor thought it might have been a bison reborn (though, the conductor knew, the buffalo were all gone.) But what rough beast was this? The stallion and his string of mares, their foals and yearlings planted themselves near the iced boxcar, as if to cool themselves from their runs.

The black Bucephalus type stallion quieted his herd as they crowded the gray man’s cart. So frozen that ice was forming on its outside, the mustangs’ snorts and whinnies formed a cloud as they surrounded the rail car. The stallion reared and gave out a fierce cry, the moon rippling his brilliant, perfect coat, with shimmering, oily highlights. The white star on his forehead matched those shining above him. Then, with as much disdain for regret and reflection as his friend inside, the stallion bolted away from the tracks, his string of wives and children and their children, dutifully followed.

Inside of his dream, the gray man said, “Good to see you too old friend, good to see you too.”

…

In Kansas the train came to a halt. It was a scheduled stop, meant not for passengers but rather for freight. The conductor, wary already of the only cargo on this trip which mattered, bade the workers be quick, be steady. He need not have said anything at all, for even as the wheels ground and hissed to their halt, as the smoke cleared and blended with the ice coming from the gray man’s cart, a howl, a scream, a cry of both horror and pain came thundering out from the ice. “Don’t stop in Wichita!” Over the plains and valleys in the endless distance which is the Kansas horizon, lightning flashed. As the conductor grabbed his brake for steadiness, the voice returned. This time, lower pitched and far, far more terrifying. “Just, don’t,” it rumbled, thunder from within the cold.

Bewildered, the conductor looked at the man in the black fedora sitting with him in the locomotive–looked at him for some kind of permission if not guidance.

“You heard it just as well as I did,” said the passenger.

The conductor looked at him helplessly and asked, “What about the freight I’m supposed to pick up here?” But the only answer he received from the man in the black fedora was a stony stare. The conductor, knowing better than to ask a second time, wound the train up once more and Wichita was nothing more than a momentary memory. God almighty thought the conductor, how he hated Axes.

…

The rest of the trip was uneventful. There would be no more stops, no more horses, no more Wichitas. With a great sense of relief, the conductor eased his mighty engine on into the Elmhurst rail station, miles west of downtown. “This is correct?” he asked the Axe. The Axe, his fedora nearly covering his eyes, barely nodded. The conductor nodded back, but then found the courage to ask, “Why here? Why not go all the way into the rail yards in the city?”

The Axe, not looking up from his paper, muttered, “When you come into Chicago, you come in quietly. Or you leave quickly with a lot of noise.” The conductor decided not to ask any more questions.

A long, black sedan waited for the Axe and his package, the gray man. Several yard hands and railroad workers pried open the now frozen over rail car, this was done with not a little effort. Growing tired of the delay and growing tired of the conductor, the Axe stood over the men, smoking with a sense of dread. Seeing him, the workers doubled their efforts and with great aplomb slid open the door. Immense fogs appeared instantly as the frozen air inside hit the warm evening air of provincial Elmhurst. As the men stood, their mouths agape, the air turned white all around them until they felt they were standing in a cloud. The engine, beating and sweating, churned and choked, wanting to finish its own journey.

Undaunted by the glazed air, and completely oblivious to the workers, the Axe walked up to the now opened rail car, the cherry of his cigarette the only marker of his presence. Through the haze, he ascertained the gray man, who, impossibly, was now free of all of his bonds, and sitting upright. The gray man, his tricolored eyes intense with purpose cut through the clouds and eyed the Axe.

“I trust your sleep was pleasant enough Lou,” said the Axe. “Welcome to Chicago. There be monsters here.”